This essay was written in collaboration with filmmaker Jacob Saul as part of a series of video essays for pride month. You can hear me narrate it here:

I am one of the first defenders of Alice Oseman’s Heartstopper (2022). Having worked in a youth centre around the time of the release of its wildly successful television adaptation on Netflix last year, I was an observer to the immense good the show did for the attitudes of young people. Triggering a movement of ferocious acceptance among young people towards normalisation of LGBT identities, Heartstopper encouraged a boldness in their empathy as well as in their personal relationships that is exhilarating and stirring to watch.

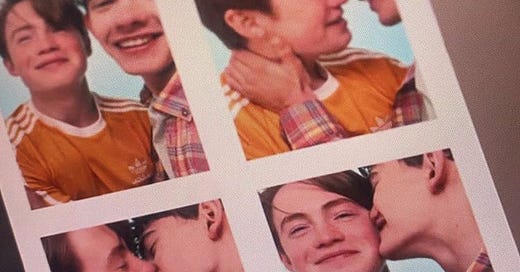

It approaches young queer identities and relationships not only with realism, but with a sense of dignity and positivity rarely granted to the typically tragic LGBT narrative we like to tell ourselves. It represents diverse identities and destigmatises queer relationships, refusing to acknowledge the prevalent hyper-sexualised image of queer people. As well as this, it’s a show suitable for all. Heartstopper refuses to play into the belief that LGBT identities are explicit. Most importantly, the show was anything but niche. Attracting an enormous fanbase almost overnight, those who weren’t following the romance of Nick and Charlie became the outliers. It’s because of this show that queerness among teens is as welcomed and as safe as it is.

Considering queerness as a culture, though, perhaps complicates the conversation. Historically, subversion has been integral to queerness; we need to look no further than to cult classic LGBT media such as The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1975) and Hedwig and the Angry Inch (2001) to see that challenging the status quo in a world that does not value queer people has been central to our culture. In the past, the media produced within queer culture has acted as a wholehearted middle finger to heteronormativity. With the dawn of Heartstopper, though, I worry that we are becoming reliant on appealing to heterosexual culture and tastes in an effort to beg for the right to respect.

In particular, there is a noticeable purity culture developing around queerness, which perhaps originates within the corners of the Heartstopper fanbase. Openness towards and about sex has historically been a major aspect of queer identities in a rejection of the same traditional ideals that pathologize queerness, and yet we see sex becoming more and more of a taboo within queer spaces. In her original graphic novels, Alice Oseman explores sex within young queer relationships; following their discovery of this, the same diehard fans of the television show created public outcry due to the discussion of sex, reflective of a cultural discomfort with queer relationships. There is an inability even within the LGBT community to accept fully rounded depictions of queer love and relationships, instead opting for idealised representation that refuses to rock the boat. Queer sexuality ultimately remains taboo, despite an increasing acceptance of queer romance and identities. Discussions of heterosexual sexuality already threatens norms derived from purity culture; queer sexuality continues to be perceived as utterly deviant, questioning the status quo on more levels than one.

I don’t believe the solution to this is the inclusion of explicit sex scenes in the upcoming second season of Heartstopper. The themes of the show itself function beautifully in displaying queer romance, which deserves representation as an experience that is not inherently sexual. However, the reaction of young queer people to overlook sex as an important aspect of relationships and sexuality is worrying, particularly when other coming-of-age shows such as Skins (2007) and the more recent Euphoria (2019) approach sex as a fully-realised aspect of relationships that deserve discussion and authentic representation. Interestingly, there is much less controversy around the teen sexuality of the heterosexual characters of each of these shows.

Perhaps the vehement rejection of discussions about sex from the fanbase of the Heartstopper show comes as a response to the longstanding image of over-sexualisation and deviance faced by the LGBT community. In succumbing to the impulse to counter these biases, young queer people are denying themselves honest conversations about sex. Sex education for queer people is notoriously inadequate, and sexual violence in LGBT relationships remains largely ignored. Instead of addressing these issues, we focus on playing into conservative values of sex – the very same that stigmatised queer identities in the first place. Pandering to these heterosexual ideals is not necessarily helpful in advancing the rights and liberties of queer people, particularly around values regarding sex, which often originate from a misogynistic and patriarchal context. Purity culture has attached the notion of scandal to sex and discussions about sex, which has been used, and continues to be used, as a tool to silence women in discussions about sexual violence. In replicating these structures in our own community, we are upholding and encouraging the strength of oppressive rhetoric.

Despite a cast of characters that is diverse in ethnicity and identity, it bothers me that the Heartstopper show is so overwhelmingly middle class. It exclusively depicts teens from middle class families, ignoring the often-overlooked experiences of working class queer people. The specificity of the class of the protagonists is clear even down to the characters’ accents and choice of language – the minor character Harry Green, portrayed to be something of a villain, speaks jarringly differently to the cut-glass accents of the protagonists, using working class slang. He is clearly coded as nouveau riche. What makes Heartstopper so important to LGBT youth is its overarching positive storyline, focussing on queer joy and queer love. What ideals do we push when we take this narrative and apply it exclusively to the middle class? That working class queer youth are an unimportant minority? Or that they don’t get to have a happy ending?

This inadequacy of class representation in Heartstopper goes deeper. Pierre Bourdieu describes ‘cultural capital’, a set of cultural assets including tastes, skills, and mannerisms, all of which may serve to increase a person’s status. Heartstopper operates firmly within the realm of the middle class cultural capital, signifying intelligence of characters by equating it with middle class preferences. The protagonists are shown to be emotionally intelligent via their apparently superior tastes in film and books, as well as through costly hobbies such as Charlie’s drumming. Meanwhile, extracurriculars which may not be so associated with middle class culture – specifically, in this case, team sports – are depicted as being enjoyed exclusively by characters who are emotionally ignorant. The kindness and acceptance of Nick, the sensitive rugby player, is shown to be the exception that proves the rule.

Outside of its plotline, the show is designed to cater to middle class aesthetics, perhaps signifying its own goodness and progressiveness through its conformity to ideas about cultural capital. Set design is a major aspect, and is perhaps most apparent when we see the characters in their own homes, which are invariably large and bright, carefully furnished with possessions that reaffirm the class and status of the residents. Whether or not this decision was intentional, it is certainly as deliberate as every detail of every television show is.

There are benefits to this approach. In some ways, it could be one of the causes of the show’s massive success. Although Heartstopper approaches queerness and queer relationships, it does not necessarily ask the viewer to question any preconceptions – all it requires is a level of acceptance. Because of this, Heartstopper is not a difficult watch, particularly for groups who may already be struggling with certain biases against LGBT identities and against aspects of queer culture. Because no singular piece of media is capable of offering every queer perspective, Heartstopper plays it safe, taking only a step outside the comfort zone of the heterosexual culture. By playing into mainstream aesthetics and storylines, non-LGBT viewers may feel that they are able to relate to the characters in certain ways, as the experience of the characters is not so far removed from dominant heterosexual culture, and does not attempt to challenge it in any meaningful way. Instead, Heartstopper attempts to integrate queerness into the worldview already held by many of its viewers.

Without having taken this approach, Heartstopper may well have become another niche queer love story, reaching only a fraction of the audience it has amassed by appealing to dominant culture. Its audience of young teens are likely to have their media consumption restricted or otherwise influenced by their parents. In appealing to their parents’ biases, as well as by avoiding subversive content in its storytelling, Heartstopper has slipped sexual and gender diversity into young people’s media. Because it is highly accessible it has easily filtered into the media consumed by their parents, creating a safer environment for young queer people to explore their identities, and inspiring the next generation to reconsider their attitudes towards queerness.

Even so, it is disheartening to see the watering down of queer culture following the release of Heartstopper. Many young queer people entering the community are approaching LGBT issues without the nuance that queer culture calls for, ignoring aspects of queerness that may challenge the status quo in a way that threatens comfort. Having been built in the context of oppression, real queer culture requires a radically non-judgemental approach which is in profound opposition to dominant middle class heterosexual culture. Heartstopper does not equip young queer people to take part in the existing community, instead encouraging them to turn back to the safety of the hegemonic culture. It could even be that the show actively threatens the existing queer culture, as it does not depict or respect the history and values behind the culture, instead pandering to heterosexual aesthetics and storylines.

There is no easy answer to the issues produced by Heartstopper for the queer community. We should not deny queer youth the safety and acceptance produced by the show. We cannot watch generations of queer people continue to experience the same oppression and abuse – stagnation is not an option. But it is painful to watch the established queer culture be undermined by attempts to normalise LGBT identities in the mainstream. Much of this culture was forged as reaction to suffering, to create the queer joy that has been so radical in the past. What Heartstopper fails to appreciate is the meanings behind queer culture. Despite this, it’s impossible to ignore the overwhelmingly uplifting response the show inspires. Its popularity has changed the game for young people, penetrating a deep culture of shame around queerness.